We have been put inside a consciousness that seems to give no thought to others any more a consciousness ‘plagued’ by the senses, that would rather not pay too much attention to what is around it, because when it does, the world’s too much: you can hear ‘the seeds … moaning in the gardens’. We have toured the heroin houses, met the ‘ghost-complected women’, cruised the city in the company of friends sketched so briskly as to resemble already the chalk outlines of the dead. We have encountered myriad mysteries and barely seen tragedies. But the hunch is this is Chekhov’s rifle: it’s going to be fired at some point in the next dozen pages.īy the time we get back to that gun, there are, by my count, at least three conventional plot twists. It’s a cheap gun - ‘so cheap, I was sure it would explode in my hands if I ever pulled the trigger’. And then, we are shown the narrator’s gun.

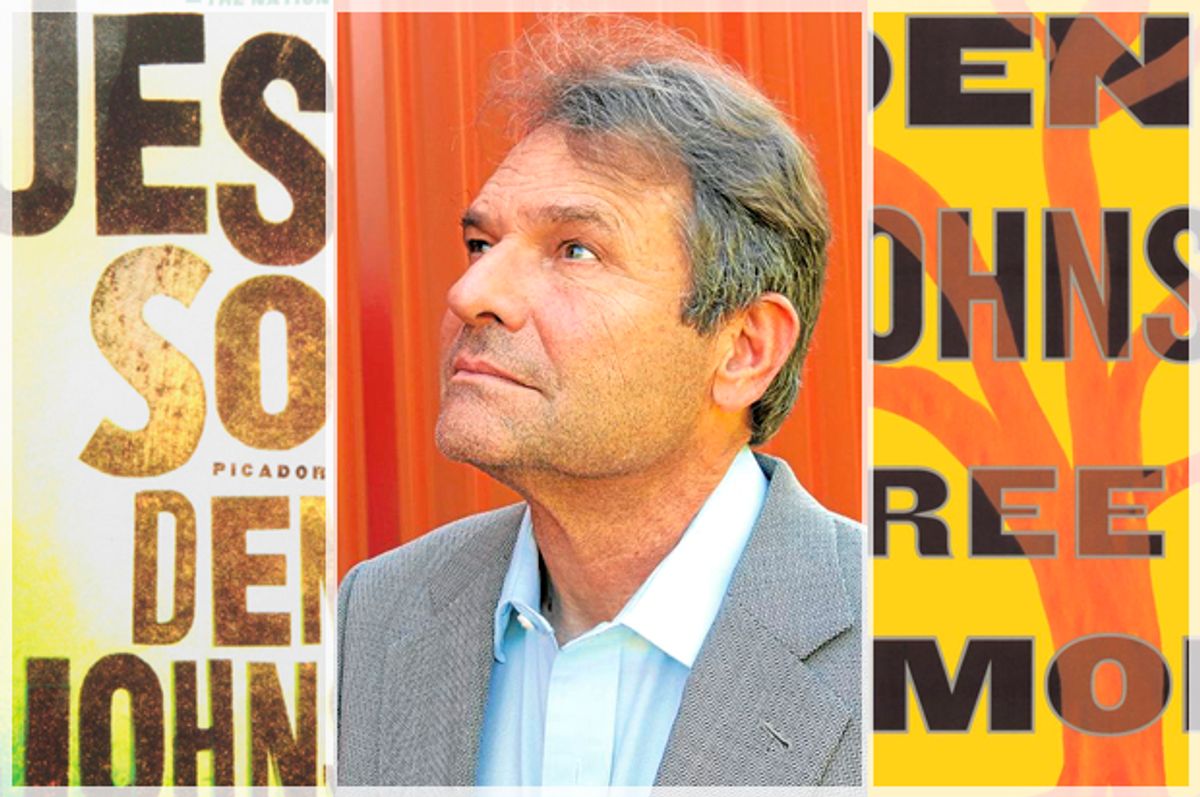

Who is he, and how are we going to get rid of him?Īnd we are presented with a threat: a jealous boyfriend - ‘a mean, skinny, intelligent man I happened to feel inferior to’ -is on the narrator’s tail and is bound to make ‘something painful and degrading happen’ soon. Within fifty lines, we are presented with a mystery and a problem: ‘the first man’ - a junkie who will not, or cannot, speak - appears in the back seat of the narrator’s little green Volkswagen. Narrated by an unnamed man reeling from his addiction to heroin and alcohol, it is, the critics say, a book which brought the ‘dulled sensibility’ and ‘too-big sentimentality’ of the addict to life, risking insensitivity to make something vital and new. Four years later, it would feature as the second story in Johnson’s Jesus’ Son, which a certain portion of the global literati will tell you is the standout volume of stories of the last quarter-century. ‘Two Men’ first appeared in September 1988, in the pages of the New Yorker magazine.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)